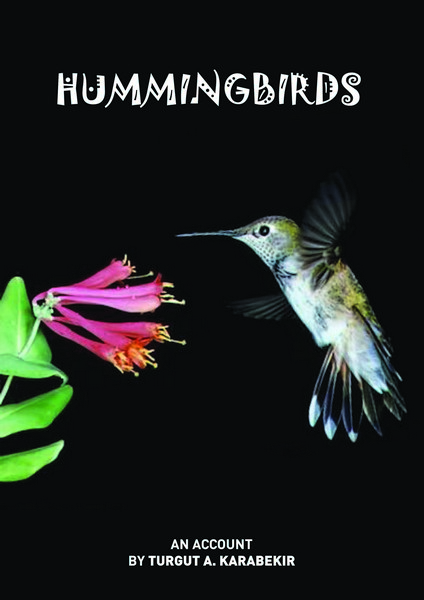

Hummingbirds

Hummingbirds must stay afloat to feed themselves,

Hummingbirds must stay afloat to feed themselves,

While afloat, in some species

their heartbeat reaches 1260

beats per minute,

their wing beat reaches 180

beats per second.

A hummingbird must collect nectar to be able to fly, and must fly to be able to collect nectar.

For us the question is: Do we live for working? or Do we work for living? Then The key to happiness is to be able to make the right choice, at the right time.

Chapter 1

A new beginning.

From Kuma’s log:

October 01, 1976

06:15 AM

Kuma was covered with a wet blanket. It has been a very humid night, and the morning dew condensed over everything in large droplets. Although it was now daylight, the sun was still behind the hill over the harbor, and it had not yet risen.

Tiny Silivri harbor was quiet. Other than a couple fishermen preparing their nets, nothing moved. Even the ferryboat had shut its engines off for the night and was sitting still. Kazım and I didn’t talk much. We mopped the decks and the bright work with towels as quietly and quickly as possible. I have always been meticulous about being orderly and clean in the boat. For me this has always been part of the pleasure, not a burden in taking care of Kuma. It has given me great satisfaction seeing her in good shape and clean. I also believe that order brings safety.

I want to get away from this tight harbor as soon as possible, but as usual, everything had to be set straight before we were ready to weigh the anchor. With our small size next to the huge ferry and our aluminum spars, we looked very out of place. We were “stern to” the quay as is the custom in the entire Mediterranean. There was room for only a few boats in the harbor. The chart was not very detailed, and if it hadn’t been for Kazım’s advice, we would have touched the bottom when we came in last night. Four lengths away from our bow, there was shallow water. The harbor was protected from the northerly winds Poyraz, but it was completely open to southerly winds, Lodos.

At 6:45 AM without disturbing the piece of the harbor, we collected our lines, weighed the anchor, and headed for the open sea. As soon as we left the harbor, I felt a lot better and in control of things.

Autumn was starting in Istanbul, and the morning air lost the summer warmth. It felt crisp and rejuvenating. I could sense that it was going to be a nice day. It was already serene and scenic, except for the annoying noise of our diesel engine. I could not stand it, and I cut it off after ten long minutes. Then, everything turned back to tranquility. We were on a glassy sea. It was deep, dark blue. This was the blue water that I missed when I sailed in the muddy Chesapeake Bay for many years. Again I looked into its depths with admiration and respect to its power.

Around us everything was standing still. While we were coming away from the shore, the sun started to rise over the hills behind the harbor. I started to feel its warmth on my skin. It was a great feeling. This was an exceptional moment that I would never forget.

With the sun, came a whisper of a breeze from our port quarter, not on the water but on our faces alone. It seemed to be afraid of disturbing the surface of the velvet sea. We put up the Genoa and the mizzen. Like in a dream pushed by an unseen hand, we were gliding over the glassy sea. A barely noticeable “ V ” developed off our bow.

The sun was rising with all its glory. The land was still dappled with shadows, but the houses were starting to shimmer under the sun’s rays. They stood prominently on the land as we did on the water. In front of us the morning haze was barely visible. It felt like we were being taken into an unknown world. It was as if we were under a spotlight creating our own environment. With, deep, blue water beneath us and the foggy mist beyond our bow, our white sails illuminated against the blue sky. At that moment, I closed my eyes and imagined flying up to the sky like a bird and looking at Kuma rocking in the scintillating cradle of the sea.

It was like a dream, but then, I realized I was alone and felt isolated. I did not know if this feeling had occurred from not having someone close to me to share this beauty or being on the threshold of a new beginning. I daydreamed for a while, and my melancholy sunk in even more.

Out of nowhere a solitary butterfly appeared from a few feet from our hull, clapping its multicolor wings with the joy of finding us. The truth was, I was the happy one to have found another companion in my loneliness moment.

This leg of my journey started yesterday from İstanbul, Suadiye, Korupark, where Kuma was anchored for the past three months.

I had planned to start a month earlier but extensive renovation that was being done at my apartment flat at Suadiye Karabekir apartment flat near Korupark, could not have been completed as scheduled. My other reason to start the trip late was to avoid running into the end of the August Lodos storm at the Marmara Sea. This delay had other major effects on our trip that still saddens me to this day. First of all, I had always planned to make this trip down to Bodrum with my boyhood friend and sailing companion, racing buddy Ziya Ergün: I would not have dreamed it any other way. But because I was late, and he had to referee at a regatta in Sweden, he could not come with me. At the time, I had no idea that the entire stay of Kuma in the south of Turkey would be plagued with unforeseen obstacles, and I would yearn to share the experience with him.

Then, my good friends, Tahsin Doruk and his wife Nimet, volunteered to come along. This, in fact, was an unexpected blessing. We made all the preparations, including Nimet’s special cooking. A day before our departure, a terrorist group who was protesting their wages had planted a bomb at the entrance of Tahsin’s factory in Pendik and almost got his father killed. Under the circumstances, they could not leave town. With this new unfortunate development I became desperate to find someone to come with me and not having any choice in the matter, with the generosity of Yilmaz Akar, I ended up starting the trip with his motor yacht’s hand Kazım. A young, decent seaman from the island of Marmara who had never been on a sailboat like Kuma had no idea of sailing or boat handling other than steering a motor yacht. As it turned out, he was quick to learn to change sails and was good at tying the boat at tight harbors. Later this proved to be a misconception on my part. Anyhow, that day I was glad to have found him.

On September 30, 1976 at 09:30 AM we dropped off our mooring line and started out from Korupark with no one to wave us goodbye. I was terribly sorry not to have Gönül with me, and at the least, come to the shore, and wish me well on such an important event of my life. She stayed home. I am sure worrying about me to start something she thought I could not handle.

For me, this was not the beginning of just a trip: it was by all means the beginning of a new phase in our lives. Korupark has always been a very special place for me, for all practical purposes this is where I grew up. From 1940 until I came to the US in 1959, I lived there. Our house was on Bağdat Caddesi, at the corner of Çınarlı Yol, one block from Suadiye, to the east. Our property was two blocks from the seashore, and the property there belonged to Ziya Ergün’s family. Because of our close relationship with him and his entire family, we used the premises as our own and Korupark became a second home for me.

During the seventeen years that passed, lots of things changed in Korupark—the most disturbing was the water was not clean anymore. The crystal clear waters that we used to know stone by stone, reeked of pungent, dark brown liquid, and the water was thick with overgrowth of abominable vegetation. Right in our little cove a 24-inch pipe continuously dumped in raw sewage. The bottom was covered with black silt that you did not want to touch. It was out of the question for me to drop anchor there, and although I was going to be there for a couple of months, I had to go through the expense of building up a permanent mooring. So that is why our departure was quite fast and clean.

Our trip started with very light SSE wind, the “Körfez” common for the area in the early hours of the day. Then it slowly started to shift to Imbat from SSW. We put up the sails as soon as the wind shifted and cut the engine off. It seemed like a perfect start and the beginning of a great sailing to Marmara Island, almost due west, beating in to a 10-12 knot wind, a fresh breeze on our faces. Kuma’s bottom was clean, and we were doing quite well and passed the Bosphorus current before the dead seas started to come in, and the wind started to die down. This was the indication that the wind was already dead to the west of us. Surely enough we had to drop the sails at 1400 hour and started the engine. Normally, in the afternoon, the wind shifts to NNE “Poyraz” and blows 12-16 knots until the sunset. But we were already in September, and I knew to steer a middle course to make my choice later. Soon the dream of having a moonlight sail to Marmara Island was to be abandoned, and I decided instead to go to our second alternative—Silivri Harbor.

For all the years that I sailed in this region, I had never been out in the open Marmara Sea beyond the Prince Islands basin. My father, a sailor in his own right, somehow never felt it was safe for us to venture into this area with our fifteen foot, double-ender, centerboard dinghy, even after I became an accomplished sailor, and a champion, including regattas in the tricky Bosphorus.

In those days, we did not question the wishes of our elders, and it did not bother us to obey them without question. Now after many years of yacht sailing, racing, and ocean cruising, it was a pleasant event for me to be on the waters where I was not permitted before. This brought back lots of memories, and I found myself daydreaming with the bang, bang of the engine drumming in my ears. We were taught to believe that our parents knew better. I adored my father’s past, admired his experiences, and learned many things from him, including most of my hobbies. To do things that he taught me came naturally to me, and I was quick to learn. On lots of subjects, I improved my knowledge by reading about them and thereby excelled in most of them. I knew he knew this, and I made him very proud and happy. That made me happy and gave me confidence in other things in my life—a confidence that failed to pass on to my own son.

We started the engine at 1400 and made a landfall to Silivri at 1900, right before dark. It was a tiny harbor built mainly for the ferryboat and for few fishermen, definitely not for yachts like Kuma. With the guidance of Kazim who knew the harbor, we sterned into the quay, had a quick dinner and turned in early for the anticipation of an early start the next morning. The day’s run was 42 N. Miles and we averaged 4.42 nm/hr.

Silivri in those days was a little town, famous for its yogurt. When I was a kid, there were street vendors who went around the neighborhood with a long pole on their shoulders carrying a round, flat, glass-covered container hanging from each side of the pole, which would hold the yogurt. The vendor would weigh a plate with pieces of stone and scoop up the yogurt in thin layers with a flat spoon and put it on your plate. Back then, they used hand-held scales, and if you were not careful, most of them would cheat you by holding the handle just a bit off the vertical and thus sell you less for your money. Nevertheless, the taste of that yogurt was a wonder, especially the top layer where the cream would form a yellowish skin. But most of the times, even though it was protected with the glass cover, it would collect dust from the street, and we would not be allowed to eat it. The buyer would often argue with the vendor to not put the top, thus increasing the weight that he would pay for. Oh the good old days! I wish we had that old dusty yogurt rather than our Colombo yogurt in their plastic containers.

I had been in Silivri before by land, behind the harbor in the hills for quail hunting. About twenty years ago, between Silivri and Tekirdag we had a good day with quite a few quails and the biggest rabbit, a hare, which I had ever seen. This was certainly a trophy for me, and I had the skin dried out and used it for many years as an ornament. Now Silivri became a town on its own merit, crowded with multi-story buildings, shops, and major highways that ran through it. That quaint town is gone, and as common in new Istanbul those picturesque houses glimmering in the morning sun were supplanted by boorish and grayish looking haphazard developments.

As the morning sun rose in the sky behind us, the mist in front of us started to burn out, but somehow the haze where Marmara Island stood never cleared out. Most of the day, until the late afternoon, until we got close to the island, it stayed behind the mist. This created a rather funny discussion between Kazım and me. He was born and raised at Marmara Island. He was supposed to know everything about it. He had been there many times with Yılmaz’s motor-yacht, but he could not figure out our course. He kept telling me I was on the wrong course and should steer fifteen degrees more to the west. Well, I trusted my chart and my compass, so I proceeded to allow for the current to set my own course. This certainly was not a happy start for Kazim. When the haze finally lifted and we found ourselves exactly where we should be heading for the western tip of the Island, Kazım didn’t say anything. However, I realized at least he learned that I knew the business. Sailing to Marmara Island turned out to be a twelve-hour trip. Because winds increased up to 12 knots in the late afternoon, our daily average speed was 4.16 knots.

By the time we pulled into the harbor at 18:45, it was already dark with the wind blowing 16 knots and gusting to 20. Kazım knew the harbor and directed me in. But as it would later become apparent he would only do what he had done before without due respect to Kuma and her small size. Before I knew it, I found us tight up, with fenders, against a concrete quay with the wind constantly pushing us onto the fenders. I did not like it at all. We were also on the main and open side of the quay, and if another large boat were to arrive during the night it may just tie-up next to us, sandwiching us between the quay and its own side. After some arguments I ordered him to cast off and with a lot of difficulty we managed to go and tie-up at the protected side of the concrete quay. The next morning there was a 60 foot ugly rusty steel fishing vessel where we were before. Kazım did not say anything.

That night he went to see his family and I was not sure if he would show up in the morning after two flops in one day. But with half an hour delay he showed up with his eyes red. I guess they had a few drinks the night before. The wind blew past midnight and slowly died down to a gentle breeze. It was a pleasant night with a bright moon overhead, and I was actually happy to be alone. Once in a while a rogue gust would come down from the high hills above the harbor, bringing the dust with it and making a muddy mess of the decks. For a while I thought of the possibility of being robbed, but not having any choice in the matter I checked my SW 38 and went to sleep.

October 02, 1976

The morning had all the signs of a windy day. Kazim had no idea of predicting the wind. It was actually very surprising to me to have a local fisherman of the area to have no idea of the conditions. He must have been away from the island for a long time. We started at 09:30 with a gentle morning breeze, which soon turned to be a fresh Poyraz, and blew a perfect 12 knots the entire day. After clearing the periphery islands of Marmara, I set our course directly to the entrance to the Dardanelles at almost due west. Conditions were so perfect and steady that I was compelled to set up a double Genoa, one from the head stay tacked to the spinnaker pole and one with its own wired luff tacked to the end of the boom. I dropped the mainsail and set up the staysail in its place and also kept the mizzen. It was a bit tricky to keep all of the sails working properly, but I managed to do so the entire day without difficulty. The blue sky was decorated with cotton white clouds; the sea was not very choppy which was perfect for Kuma. We sailed all day with the wind slightly to the starboard of our stern. It was a perfect sailing day out of the textbooks. Kazım fixed my lunch, and I kept steering. Kuma is very good at steering herself without my help on the beat but not so good at the run. It would have taken lots of trouble if we had not kept the sails filled with the complicated combination I had. It all worked out great. For me it was an extremely satisfying day, but I don’t think Kazım felt the same way sitting and doing nothing. I didn’t think that he had the sailor’s serenity in him.

Nevertheless, we rolled over blue waves with tiny white caps and reached the entrance to the Dardanelles in t the late afternoon. We dropped our double headsail and the staysail and raised our main in preparation to enter the Narrows. At times, the wind increased up to 20 knots. I have to admit that I was excited. Going through this historical narrows with my own boat I believe I had every reason to be. It was much more exhilarating than going through Hell’s Gate and New York City. Sailing wisely, certainly you had to be very careful, and take into account all of the incoming as well as outgoing traffic of large and small freighters as well as negotiate the current. At places with the 3-4 knots current added to our own speed, we reached 8-9 knots. Although it does not seem much when you think about a car’s speed, in a small boat, however, that is quite fast and your destinations in a tight Narrow with quite a few sharp bends come very quickly. I followed the European shore very closely, in some places uncomfortably close. But I knew that the Dardanelles was the one place the British Admiralty knew very well, and I was sure that their charts would be accurate.

The heroism written on these hills cannot be described with my simple words. You must read many books in order to appreciate how one’s own enemy became one’s admirer after a few days of torturous, bloody confrontations. The British were ill-planned, cocky, and stubborn in their pursuit to capture these hills, the gateway to Istanbul— capital of the Ottoman Empire. They brought in with them from Australia and New Zealand young volunteers to fight their inane war for themselves. Anzacs were their names. They were as heroic as the Turks defending their own country. They were brainwashed by the British to believe that this was a good cause and conquering back Constantinople was a holy Christian duty. They would understand the truth after losing thousands of troops and learning the real face of this phony “Crusade”. This was a folly of a young and inexperienced, but ambitious British naval officer—Winston Churchill. He would bitterly learn what patriotism is when Turkish soldiers were forced to defend these hills with their bare flesh and blood against overpowering forces of the allies. This would be his first disaster but not his last. Years later he would save Britain from the invasion of the Germans only after the Americans came to his aid sacrificing the lives of their own children to save Europe from the boots of Hitler’s army.

Mustafa Kemal, a young officer himself of the Ottoman army, with his genius and with the aid of brave Turkish soldiers had written in these hills a history. Their heroism has never been equaled. My uncle Cemal, a young officer too at the time, fought in this war, and narrowly escaped death by almost a miracle. Years later I would be told this following fascinating story.

At the time, my Granny was at Ankara living on our vineyard property. I was always told that she possessed a sixth sense. She sometimes would go into a trance and would say things that would startle people. I was told that on that particular day she was taking a nap. In her dream, she saw an elderly man, a saint with a white beard say to her “Cemal is in danger. Immediately sacrifice a sheep for his safety, and pray to God.” She woke up and called the help and ordered to slaughter a sheep immediately. At the same time in Çanakkale, at the hills of Dardanelle, my uncle was leading his regiment through a dry streambed. He was walking on the ridge of the streambed. He said, “I was walking on the side of a ridge, and the soldiers were below the ridge. I was trying to see what lay ahead. In an instant what seemed like an unknown hand had grabbed me from my shoulders and I found myself two meters below in the streambed. No later than a second, a bomb exploded exactly where I was standing. I knew this was an exceptional event, and I recorded the day and the time. Later I learned from my mother what she had seen in her dream and what she had done.” Thinking about all this and all the other untold stories, I found myself with tears in my eyes.

The following are some excerpts that I think start to draw a picture of the senselessness and the bloodiness of this war that was started by the British.

“To commemorate Anzac Day, the following was aired at the Radio National in recollections of Gallipolis veterans’ accounts from the ABC archives. Sue Jives reports. April 25, 2003.

Millions of words have been spoken and written since 1915 about the blood spent senselessly at Gallipolis, but few more powerfully illustrate the horrible absurdity of that campaign than the description of Australian and Turkish Soldiers who were swapping cigarettes for bully beef, amid the slaughter.

According to stretcher-bearer Harry Benson, “When it was quiet, we used to throw tins of bully beef over to them, and they didn’t think much of our bully beef, and they threw it back to us. They threw us Turkish cigarettes, which we very much appreciated.”

The survivors of Gallipolis have passed away but their stories live on in archival interviews and recordings. Their recollections capture the essential elements of the Anzac experience—the naive spirit of adventure they felt setting off to help Mother England, their mates cut down around them on the battlefield, the determination to keep going in the face of defeat and their respect for the enemy, Johnny Turk.

Infantryman Jack Nicholson recalls arriving at Anzac Cove at daybreak behind several other battalions. “They were just dropping like flies. We lost half of our battalion. You didn’t hear the shots; you’d just see the man drop. The idea of the landing was to kill or be killed.”

“The casualties were something shocking,” says gunner Bill Greer of a later attack. “We could see them advancing, our men, and they were going down like flies. We were in a terrible pickle. We only fired about one shot. Our supplies hadn’t arrived. That’s what’s called a blood bath.”

The Turks also suffered huge losses and the Australians noted their bravery. “About 30,000 Turks one day came rushing through the gullies in an endeavor to drive us into the sea,” Benson says. “They were shot down and when it was all over 3000 Turkish dead bodies lay at the head of Monash Gully. They lay there for almost two weeks. The stench was indescribable … and that is why the Turks called an armistice – to bury their dead in no-man’s land.”

It’s the small, everyday details that are perhaps the most poignant – the men’s wonder at seeing snow fall for the first time, sneaking down to the sea to bathe and get rid of the body lice, the stench and flies near the rudimentary toilet pits, and the hated bully beef, onion and biscuit diet.

“My greatest fear as a soldier was would I be a coward, would I be frightened?” says infantryman John Cargill. “But I proved to myself I wasn’t. It would be stupid to say a man wasn’t scared going practically into the face of death, but he does it just the same whether he’s scared or not.”

From the accounts of Lieutenant Cosey:

“On April 23, 1915 at Conkbayırı, a bloody battle was raging between the Allied forces and the Turks. There was only 8-10 meters between the trenches of the opposing sides. After a fierce battle of bayonets, both sides went back to their respective trenches. Soldiers were collecting their wounded that were close to their trenches. In the middle an English Lieutenant with his leg almost severed, was screaming, and pleading for help. But no one was daring to go out to help him because the slightest movement on the open attracted hundreds of bullets. At that moment something unimaginable happened. From the Turkish trench, a white underwear was raised and immediately after it a Turkish soldier came out to the open. Everyone was frozen with the unexpected appearance. It seems no one was even breathing and watching him. He was walking slowly under the pointed guns aiming at him. Turkish soldiers walked to the wounded English officer and gently took him in his arms, carried him to the British trenches, left the wounded to them and calmly returned to Turkish trenches. Everyone was frozen and not even an exchange of thanking was heard. For many days afterwards the kindness and bravery of this soldier was spoken. Not even his name was known but the memory of this event will always be known. With my warmest thanks and gratitude to this Mehmetcik.

Lieutenant Cosey later became the Governor General of Australia.

From lots of people I keep hearing how successful the British have been in world politics. I disagree. One of the better examples of it may be the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire. Without any doubt they have been instrumental in doing that. At the least they set the stage for others. Their goal was to control the straights of Marmara, western Anatolia, and northern Iraq and to stop Russia from reaching the Indian Ocean as well as to get control of the oil reserves of Arabia. Acting as the conductor to the events from the early 1900’s through 1920 they indeed caused the fall of the Ottomans, and created mediocre little Arab emirates in the Middle East. The US, a spectator back then, came gracefully and captured the oil rich regions’ wealth.

Atatürk chased the Allies out of the Mainland of the Ottomans and established the Turkish Republic on the ruins of the Empire. The world ended up with an unsolvable problem of “the Middle East” for centuries to come. After the dust settled, England ended up with nothing. They lingered in Iraq until 1935.To understand this important period of history pertaining to the Ottoman Empire as well as the future problems that will recur during your lifetime, you should read a book called A Peace to End All Peace. You will learn how uninformed the British were when they were making decisions about the future of the nations involved and about the lives of millions of people that died because of them. Their miscalculations of the future of the Ottomans and the Germans set the stage for WW2 and thus again millions more were to perish in the conflict inflicted by Hitler. Furthermore, they caused the Cold War and wasted valuable world resources until the late 1980’s until finally Communist Russia was no longer a threat to the capitalist world.

Britain should not be condoned for the miscalculations they did and the harm they inflicted on millions of people who died for nothing and are still dying in the Middle East.

We were a bit late to make Çanakkale harbor where I was planning to stop for the night and clear the Customs in the morning. The sun was already down and it was getting dark very quickly in the Narrows. So I elected to spend the night at Eceabat and head for Çanakkale in the morning. I was told that it was a little tricky to go into Çanakkale at night if you were there for the first time, especially with a boat like Kuma that does not maneuver well under power. We started the engine and dropped the sails at the mouth of the little harbor of Eceabat right before we needed to turn in. It was a well-timed operation, and I was happy with Kazım’s performance. The harbor was well lit with the lights of the tied-up ferryboat, and we had no trouble to find a place. Again we anchored and sterned-in to the quay. It was a peaceful night with a bright moon overhead. Time was 21:30 and the day’s run was 64 N. miles with an average speed of 6.24 miles. I had dinner in Kuma and turned in early for an early start the following morning. All night we were disturbed by the sound of big trucks passing from the road immediately above the harbor.

October 03, 1976

At 08:00 we left Eceabat under power to cross the straight to Çanakkale where we needed to clear the customs to go out of Turkish waters. There was another reason to do this very early in the morning. I was cautioned that the officials could hold me for hours for no apparent reason expecting a bribe. Well I was not experienced in this kind of things and had no intention to start now. So I timed it as such that I will be knocking on his door at off-business hours and asking some overtime work therefore making a justified payment for his time. If you are thinking what the hell, well you are correct for doing so. But what you have to realize is I had no alternative than doing what I did or risk starting late in the day and not reaching our next harbor in daylight. It all worked out just as I planned. I knocked on his door and a sleepy fat man appeared at the door. I gave him the story about his special time and everything. He let me in. I already stacked some money into our official papers when I handed it to him. With no surprise he looked at the money, pocketed it and with his filthy handkerchief blew his red nose, developed from the cold, and stamped our papers and with out saying a word walked out of the room. I was especially careful not to touch anything on my body before I washed my hands.

The piers that we tied up to were under the effect of a strong current. We already had some difficulty in maneuvering Kuma without scraping on her sides. But with Kazim’s help and knowledge of handling mooring lines it was not so bad. Getting out of the harbor was of course easier, and by 09:30, we were on our way in a few minutes. It was already a windy day blowing 20 knots from NE, and it looked like the wind could pick up as soon as we cleared the Narrows out into the Aegean Sea.

Again it was exhilarating sailing with the same historical surrounding in the morning light. We put up the main and the Genoa. With the current adding to our surface speed of five knots on the bottom we must have been making at least eight knots or more. I could clearly see the opening of the narrows and the change in the surface of the sea. Just beyond the turbulence where the water was pressed together for one last time emptying the Black sea into the Aegean after a long journey. Smooth waters of the narrow were changing into rolling seas about a mile ahead. We dropped the main and put up the mizzen sail in preparation for the conditions to come. I have always been very cautious of not carrying too much sails. I know Kuma well enough to know that too much sail will not be good to anyone. At 10:05 we had Karanfil Point abeam, and 10:58 Kum Point abeam, 11:05 Ilyasbaba was at our stern.

By 11:00, we were in the Aegean. There were three to four feet seas running with us coming out of the narrow. When we turn southward toward our next destination and got off about a mile from unfriendly rocky shores of Çanakkale we started to pick up the actual wind that increased soon to 20 knots gusting to 25, and wave action stated to increase. And with each mile away from the narrows the wind picked up speed and the waves started to get bigger. I dropped the Genoa and put up a #2 jib. With six to seven feet of seas rolling at our stern under #2 jib and mizzen, we were making 6.0 to 6.5 knots. It was quite difficult, boring, and tiring too. It was difficult to keep her from yawing in the short wave action of the Aegean Sea.

The Aegean Sea happens to be one of the most uncomfortable seas if not one of the most dangerous, after the Mediterranean. A fresh breeze could build up to a storm in no time and with the short wave length it can be very risky for a small vessel to be out in the middle of the blow. It can blow night and day for days, and it is quite common for boats to be stranded in the harbors for more than a week at a time. That is why the Phoenicians and the Greeks used flat bottom, light boats making them able to beach the vessel anywhere as soon as the storm hit them. If they were not able to reach the shore they just floundered or hit some rocks and sank. That is why the Mediterranean especially the Turkish coast is full of shipwrecks. Storms usually blow toward Turkish coasts and in most areas the coasts are covered with unfriendly rocks. If you manage to find a beach, most with gravel, you will be lucky. If not, the end is already written. Save your life.

In those days, boats carried a few round pegs about four to six inches in diameter and about six feet in length, and the sailors dropped them in front of the boat at the beach a few feet apart. Without much difficulty, they pulled the boat to the beach on them and waited there until the storm blew itself off. The vessel had a short mast just enough to pull up the pole of a triangular sail that was easy to take up and easy to drop. The short mast had no windage and could be taken down as well with ease to establish the stability during the blow. Most of the boats also carried oars in various number and sizes. Some were manned by slaves who were captured from confrontations with other vessels or during raids on seaside settlements. However, most of them used the oars just to get in and out of the coves or to maneuver the boat in the harbors and rivers. Their main way of propulsion was sails. Boats did not have a keel and did not carry fixed ballast. Most of the time the cargo they carried constituted their ballast. They would put the heavy items, like metals, iron, copper, lead, glass on the very bottom of the vessel and put the lighter stuff on the upper parts. Most of the cargo was carried in clay containers. We now call them amphora. They were shaped narrow at both ends and had handles on both sides of the upper part. The oldest ones date back to 3000 B.C. and were found at Troy. Looking at their shape, experts can tell when and where they were made. The ones used for carrying water were porous to keep water cool and the ones for carrying vine were coated on the inside with pine pitch while the ones carrying olive oil were coated with gum or wax. They came in various sizes. Most of them were about two feet in height and about ten to twelve inches in diameter. They would be stacked on top of each other in layers with hay between them as cushions. It was quite common to have three rows on top of each other. Some boats had two tier decks and would carry six rows of amphora. One can see a perfect example of these vessels in the Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology, without any doubt the best in the Mediterranean.

Considering over 5000 years of commerce from all the way from Alexandria, Egypt to Troy at the Northern end of the Aegean and even to the Black Sea, one can understand the richness of the Turkish waters in archeological underwater sites. After all, we know that none of these boats survived the elements of time, and most of them ended up at the bottom of the sea with their last cargo. A few years ago we were fortunate enough to have seen one in Kadirga Bay in Marmaris when we went to visit Vedat. We enjoyed the feeling of being in contact with this several-thousand-year-old, sixty-foot long vessel broken into two sections after having hit the rocks at the south eastern end of the bay. It was a great day, and I am sure Sean and Cem also will remember this great occasion.

Within an hour, our rudder mechanism developed an unpleasant sound. I could not trust Kazım enough to give him the wheel in these tricky sailing conditions. After examining the apparatus under the cockpit floor and seeing nothing loose or broken I decided to examine further in Bozca Ada where I had no intentions to stop over. I altered my course slightly and headed for the harbor. I also wanted to see if there was anything wrong with our rudder. We pulled into the harbor with ease and tied up to the quay. In the harbor, the wind was battering us with gusts that reached 25 knots. It was only possible to tie up with an anchor and five lines. I didn’t like the conditions at all. The water in the harbor was quite uninviting, sort of murky. It was blowing hard, and I did not feel good about diving there and getting sick. I thoroughly examined the entire rudder controls and looked at the rudder itself from the top. Seeing nothing wrong, I decided to proceed to our next possible anchorage where it would be friendlier to examine her from the water.

Regardless of the unfriendly atmosphere of the harbor, it was already early afternoon, so I decided to stay for the night. Our day’s run was 25.4 N. miles, and we averaged 5.64 knots. Bozca Ada is famous for its vineyards and vegetables. From the harbor, it looked like an abandoned place without much going on.

October 04, 1976

We got underway at 07:10 hours and met the same conditions as the day before, except by 09:30 it started to gust up to 30 knots, at one point the odometer read 37, and I got Kazım to get the storm jib ready. Swells were about 8 feet at times. Kuma was riding the waves beautifully with ease, without a drop of water coming onto her decks. Our speed, our sail combinations, and the wave action must have been just right. Conditions remained the same until we rounded the Baba Burnu where we changed our course 90 degrees to almost due east entering the straights between Midilli, Greek island of Lesvos and the mainland of Turkey.

Thousands years ago, when Lesvos separated from the mainland, a narrow body of rather shallow water with some rocky parts in the middle developed. At Baba Burun where one leaves the Aegean and enters the Bay of Edremit, there is a major change in the wind and wave action.

Right at the corner, the water boils and churns, and turns around itself. It is a weird sight but not dangerous in these light wind conditions. The wind had dropped to 15 knots. As a cautionary measure, I put the engine on and we rounded without any trouble. Leaving the uncomfortable running seas behind us, we entered the smooth waters of the Muselim Channel. We cut the engine off, put up the main, dropped the #2 jib, and raised the Genoa. After a comfortable and enjoyable sail, we pulled into one of the most magnificent anchorages I had ever seen.

Sivrice was a natural harbor protected from all sides with a narrow entrance at south. It was like a man-made lake with crystal clear waters and a white sandy bottom with twelve feet of depth. As soon as we anchored, I changed into my swimming trunks and dove over to see what was wrong with the rudder and our propulsion. As soon as I went in, I was overcome with fear. My first observation was how clear the water appeared and how flat the bottom was. The second was how far I could see. It was almost endless. My third thought was that scared the hell out of me was, if I could see this far, a shark could also see me too!. I did not even think that the sharks were near-sighted and probably operated by smell rather than by sight. Anyhow I was scared and hurried to finish my examination.

The problem with the rudder was a piece of clear polyurethane sheet about the size of a dining table wrapped around our prop and hung over the rudder beyond. It was a tiring job trying to cut the thing off. It was wrapped so tight around the shaft that it felt almost like a solid piece of plastic. It took me over 20 minutes to finish the job and with continuous diving and holding my breath while I was trying to cut the poly it exhausted me a great deal. I was glad to come up and get into some warm dry clothing.

If I were with a friend at this place, I would have stayed overnight. In those days, the place looked like it belonged to just a few fishermen who had their kayiks and nets on the shore. There was no one in sight, and at the northern side of the cove, there were only a few old fishermen’s houses. I thought that if this place were discovered and got inhabited, it would quickly become polluted and lose its serenity and untouched beauty. There are no equals to the human species when it comes to destruction of the natural habitat. We always manage to cut the branch that we happen to be sitting on. I was sorry to leave this exquisite place so quickly.

Unfortunately, when we came out the wind dropped to 5 knots and we had to motor the rest of the day. However, because of the unplanned stop, we were a little late to reach our destination, Ayvalik harbor, Ali bey Island. The sun was setting down when we finally passed the periphery islands and pulled into the Ayvalik Bay at 18:00. By the time we were tying up, it was already dark. Kazım said he knew the area well, and he asked me to steer to the west of the bay to a pier that looked deserted instead of going to the front of the town where other restaurants are. I must have been quite tired after a long day and I accepted his suggestion without argument. I definitely would have anchored rather then tied up to a quay. I should have. Kazım had us anchored and sterned into the quay at the head of the pier. He had a nice way of adjusting the lines, and I was fooled with his tying skills. I should have known better. We went out and found a greasy restaurant at the foot of the pier where obviously the fishermen eat. We had fried local smelt. We were hungry and it was quite good. We turned in early in preparation for an early start in the morning.

October 05. 1976, The little “big bang”.

It has been a peaceful night but not a peaceful morning. What had seemed like the deepest part of my sleep, just before the sun was up; I walked up to a terrible bang. Without knowing the magnitude of the catastrophe I rushed out of bed with my underpants out of the cabin, to see if we were sinking. What I saw was a fisherman’s boat’s bow rise up over to our deck on our starboard rear quarter, right in front of the spinnaker winch. I was looking at this awful sight and to the face of a fisherman as startled as I was. Folloving me Kazim also came up and we asked the fisherman to shut off his engine. Wiith Kazım’s help we slid the bow of the boat back down to the sea. By sheer luck, the boat had an unusually slanted bow. This was so uncommon in these waters that it must have been a boat probably made from a Greek model. For this reason and for this reason alone Kuma was saved from having a gash on her broadside. The damage was to our gunwale and its trim. It was nevertheless an ugly looking scar on the sparkling bright work and fiberglass decks of Kuma. I was outraged and devastated. I lost my temper, and I was upset with myself for being in this situation, Kazım tying us up at the pier and the fisherman for hitting us. I had no right to be. Losing my temper was my biggest mistake. It caused me to act irrationally, and I made one of the most regrettable acts of my life that I still regret to this day.

Afterwards I dwelled upon the situation calmly, and I figured that poor fisherman acted out of habit. He was tied up at the western side of the pier. In the morning, while he was half asleep, he dropped his mooring and started the engine end by pushing the tiller to the starboard in order to round up the end of the pier to go into the bay. He probably did this every morning without even thinking for many years and that an idiot would tie up at the end of the pier. Well this morning there was one.

The regrettable act that I had committed was to have him pay for the damage he caused. I did not care how much. Just have him pay. Just to punish him for his carelessness. He was a nice man. Instead of hitting me right on the nose, he paid me all the money he had on him. It was an insignificant amount for me, but for him it must have been a day’s worth of work. I did not know his name I did not care. I was still in shock and very angry. I let him go to his day’s business, and we headed off to our way.

After not too long, when my mind was clear of the event, I started to think rationally. I became disgusted with myself. At the time I thought that he was a gentleman, and I was an in-considerate bastard. This feeling still lingers with me whenever I see the indelible scar on Kuma. It was a sad way to learn a lesson in life.

After this event for the rest of the trip, for a long time to come, I could not take my eyes off of this scar, and the sorrow and shame attached to it. The happiness of the trip was gone and it was replaced with my anger to myself and my distrust with Kazım.

We left the quay at 07:30 hour and headed to Akra Light. Wind was SSW 4-8 knots, with clear skies. The day was like the day before. Nice white cottony clouds in the blue sky and a nice light breeze, at times reaching up to 10 knots. Not knowing how the wind would develop, I did not have a definite destination. Initially, I was intending to go to Izmir and visit Engin and Şeyda. However, after the morning’s debacle, I lost my desire and did not want to face anyone after my shameful act. My self-esteem was in the pits. So I decided to shoot for Kara Burun if the conditions allowed us to do so. I was tacking between Lesbos and the mainland, and at each tack we would come very close to Greece. Being afraid of being taken into custody I would raise the Greek flag when we came to Greek waters and the Turkish flag when we approached Turkey. We had to do this several times until we cleared the southern end of Lesbos and change a steady course to Kara Burun. It was a comfortable beat with a zephyr from the North West.

After Kara Burun there was a bit of chop from the west but as soon as we entered to the shadow of Hiyos, Sakız Adası the chop disappeared. With a comfortable 8 to 10 knot wind at our starboard side with full sails under perfect conditions for Kuma, we were having a great sail, at times up to 6.5 to 7 knots. This made it possible to reach Çeşme, which I had thought in the morning that it wouldn’t be possible. It was a long hall from Ayvalik to Çeşme in one day, but it certainly started to look like we would make it. Except for my state of mind, it was a very enjoyable and perfect sailing day.

We passed by barren high cliffs that didn’t provide any appreciable refuge on the mainland. There were a few islands that we passed by that I thought most would hardly provide any shelter in a serious blow. I guessed that it would be very difficult to hold anchor on the lee side of rock formations where the bottom dropped out in a steep angle. To our west was Sakız (Samos) with its lush greenery and provided us shelter from the surf in the Aegean Sea.

The sun was low in the west but instead of pulling into Balıklıova on the mainland I decided to go to Altın Yunus at Çeşme. It would obviously be after sunset, but the charts showed that the area was clear of any kind of hidden dangers and there was practically no traffic to be concerned about. After dark, when finally we rounded up to the tip of the peninsula a spectacular view was laid before our eyes. What a change this was after watching all day the barren coast to come to find this modern hotel with all its lights ablaze and a protected man-made harbor surrounded with a jetty. The harbor was full of aluminum masts, which for me was the indication that we were entering a well-visited establishment. Sure enough as soon as we passed the entrance, an elderly gentleman with a blue blazer addressed us in perfect King’s English at the quay and asked our draw. He guided us to a proper slot. The registration was made: the overnight fee was paid in a few minutes in a very civilized manner. We were shown where the facilities were. They were perfect. We filled our water tank and were able to wash the decks and get rid of the salt that was collected during the past several days. The harbor although small was modern, secure, and perfectly protected. We registered our departure time, and we turned in after having dinner in Kuma. I would have gone out to explore the hotel and maybe have a nice dinner at their restaurant for a change of pace, but leaving Kazım behind was something I could not do. Again I missed my friends. So many things would have been different if I were with them on this trip.

October 06, 1976

Our next destination was Kuşadası. Going out of Çeşme Bay, we needed to pay special attention. After rounding the tip of the little peninsula where Altın Yunus was located at our port side we passed a nice house built along the shore including the one that belongs to our friend Melih Selvili. The tip of the Çeşme Peninsula must have been extending further to the north and was eroding for many years. Now the remaining underwater rocks extended over several miles and allowed only one narrow passage close to the mainland. So I plotted our course and the location of the narrow passage carefully. This time I was not about to even consider Kazim’s expertise. I have always found it to be silly to take unnecessary risks when dealing with nature. We dropped the sails, and I motored through the passage. As soon as we were clear of the rocks, we put up full sails and began another nice sailing day. So far we were lucky to have such consecutive nice sailing days. We had a very easy and fast reach to Sarpdere Cove.

Before our departure from Istanbul, Umur Kaya suggested to me an anchorage that was out of the way of most travelers. Its entrance was hidden, and if he hadn’t told me, it would have been impossible for me to see it. I am so glad he did. With careful observation of the shoreline and some dead reckoning, without much difficulty, I found the entrance. It had been a nice day to sail under the clear blue skies and over the deep blue water with hardly any appreciable waves. Perfect sailing conditions for Kuma.

Right before the entrance, we dropped the sails and motored into a most unexpected anchorage. The entrance was to the west and was only about fifty feet wide with sharp rocks rising to hundred feet on both sides. The Narrow was deep enough for boats bigger then Kuma, about two hundred feet long gave way to a lagoon less then a half mile long and a quarter of a mile wide. The hill on the northern edge continued but on the south got down to about twenty feet heigh and about a hundred feet wide, low enough to get some ventilation from the Mediterranean behind. The water was crystal clear. There were no trees on the surroundings other than the short bushes, common throughout the southern area of the Mediterranean. This must have been a perfect hideaway for pirates as long as no one came in and cornered you like a mouse in a bathtub.

It was still daylight and I could not resist taking a dive into Nature’s swimming pool. If I had been alone, I would have dove in stark naked, to be one with Nature. I dropped our Avon dingy over and went out to the shore to explore. The most beautiful site was seeing Kuma in this most unusual and most unfitting conditions. This place should have been left untouched and only admired by the old mighty himself. Even Kuma was out of place in this magnificent surrounding.

Before the sun set, some fishermen’s kayık came in. We exchanged greetings and well wishes. They pulled to the northern shore where there was a narrow strip of gravel and started to mend their nets. They were quiet. They almost did not exist. The night had arrived before we finished our dinner. A full moon hovered behind the hill. It gave the illusion of being less than a mile away. I have seen these phenomena before but not in such proximity. It was incredible—a full moon in a dark, blue sky with its entire splendor pushed up by an unseen hand over the top of the hill. It was like a paper moon on Nature’s stage, raised above the curtains.

The water was in absolute stillness. Except for the early cooling of the air there was no wind. The water was like a mirror. You could see every pebble in the bottom of the lagoon with the light of the moon. The full moon was so bright you could almost read a book under its light. I became mesmerized with the beauty surrounding me, again alone without anyone to share it with. I was nailed to the deck and was afraid of even breathing. I looked at our stern where the dinghy was tethered. The bottom was so clearly visible that the water was almost non-existent. The dinghy looked like it was floating in the air. I lost my bearings while I watched the dinghy standing on its end and its bow hanging in mid-air. The fishermen fifty yards away in their beached kayık were having rakı and also enjoying this picturesque view in their own way. It was a night I could have only imagined in my dreams.

October 07, 1976

Reluctantly, we left this paradise and at 09:00 started to Kuşadası. After eight hours of breathtaking sailing, we reached the harbor at 17:00. Our day’s average was 5.25 knots. The new yacht harbor at Kuşadası was very organized and completely protected from any weather. We located the motor yacht that belonged to a gentleman that was supposed to have given me advice on how to handle the triptych entry problem. As I expected, the yacht was there, but there was no owner. Nevertheless, we introduced ourselves to the deckhand indicating that we may be wintering along his boat. This was the first time we were to go through customs since Çanakkale. We had some uncomfortable moments and almost got rejected. However, when we mentioned the gentleman’s name we were considered one of the guys and things got eased up a bit. A small contribution to the coffer made it acceptable.

It was early in the day and I strolled around a bit to see the change that might have happened during the past two years that I had not been in Kuşadası. It was on 1974, coming back from our “blue voyage,” that we stayed here. The town in those days was almost non-existent. Few restaurants were along the quay; the custom house had few shops; and of course, the castle operated as a Club Mediterranean resort. A Street ran along the wall of the castle with some basic shops. I went back to the harbor and picked up Kazım and took him to dinner at the restaurant by the water where we had lunch with Melih Selvili and Oktay Yenal at the start of our blue voyage in 1974. Again this was another wasted day as far as enjoying a new place with someone you like to be with. Having nothing else to do we went back to Kuma and gave her and ourselves a bath. Except for the wound on her side Kuma was in good shape. It was a peaceful night in this protected harbor just as I liked it, quiet and still. Naturally I had to go to some neighboring boats and tie up their loose shrouds banging on their masts in the gentle breeze. I never could understand the carelessness of some people in this regard. It is disturbing to all neighbors as well as to the entire surrounding areas especially when the wind blows hard. You can hear the clack, clack of the wire hitting the aluminum masts miles away.

October 08, 1976

We left Kuşadası at 06:00, with a light breeze from the west. When you sail southwest from Kuşadası, you are practically sailing into the Greek island of Samos (Sakız). Samos is only about a mile away from the mainland of Turkey. From one shore to the other, you can see people on the shore. What makes it even worse are the little islands scattered within the straight, one with a Greek flag and the other with a Turkish flag. It is a narrow passage but deep water on both sides. Because we were in the shadow of Samos, the wind was barely noticeable, and we were carrying full sails. In front of us laid Akburun at the mainland. A very impressive piece of land jutting out of the water almost at a vertical rise and reaching up to over a thousand feet. The sea just beyond the tip was a different color. The lightly rippled sea that we were motor sailing in the narrow was a dark, blue color transforming into white caps about a mile down further. I knew exactly what this meant and asked Kazım to reduce sails down to #3 jib and mizzen. He tried to complain but I asked him to wait and see why. As soon as we entered the area, the wind dropped down from the top of the mountain at a sixty degree angle to the water, whipping everything in its way. You had to hold down your hat to not lose it forever. In a few minutes after entering into this area the wind kicked up to thirty knots slamming us from the top. It was a good phenomenon to be in and I was glad to have predicted it. Kazım did not say anything. It only lasted less than an hour and as soon as we were cleared of the shadow of the mountain things got back to normal and we then changed to full sail.

We were now approaching the Meanders Delta. Between the straight and the delta, it was a smooth sail. The wind emanated from the southwest at about eight to ten knots. As soon as we entered the delta the color of the water changed murky yellow. With that, the direction of the wind also changed to the northeast coming from the plain where the river extends as far as you can see.

About twenty miles inland from the present shoreline, Ephesus is located. At the time of Efesus the city had a harbor opening to the Mediterranean. Since that time, the eroded soil carried from the plains had been filling the sea at the rate of about twenty-one inches every year. Once a bustling harbor city, Ephesus slowly lost its commercial value when the sailing vessels were unable to come in from the sea. Perinea was another harbor city on the north of the plain that also now is even further inland. Most likely this phenomenon was one of the reasons for the decline of both cities.

I have seen both of these cities from land and was very impressed with both of their splendors. Perinea, although a small city compared to Ephesus, obviously was a very organized and wealthy community. The city now sits on top of a hill overlooking the plain below. It is hard to imagine it being a harbor city. It must have had a road coming down to the harbor. The city itself had very organized streets, a nice amphitheater and a hospital, all still in good shape, lots of foundations along a steep street running to the top of the hill. Maybe the city used to extend down to the water’s edge with less durable housing and with time disappeared. On top of the hill, just beyond the temple, there were two cisterns that were fed with a stream on a higher hill beyond with sealed pipes through the lower land between two hills. One cistern was used for cold water, and the other, exposed to the sun, was for the hot water. There were lead pipes from the cisterns to the houses that some are still visible even today.

In this little city I was as impressed as I was in Pompeii in Italy. It always gives me a strange feeling to walk over the ancient streets carved on both sides with the wheels of the chariots. Every time I go to one of these places, I drift back in time and imagine being surrounded by a throng of people wearing their white tunics and sandals and peering into the doorways that opened into the colorful courtyards with their fountains running. Suddenly, a lizard darts in front of me, and I return back to the presence of the now abandoned city. Melancholy sets in.

Most peoples do not realize that western Anatolia was the cradle of the Western Civilization. Crete and Greece came after and adapted their customs and ways. When one travels now by sea, up and down the Turkish coast, it becomes quite expected that whenever you see a nice place, and you look carefully with binoculars, you always see the remnants of an old settlement. I have observed this coming down the coast myself. First I would look at the formation of the land and say—what a nice place. Then, when I would examine it closer, invariably I would see the marking of an old city. These cities were called “City-States.” Each one of them most often was an independent country, if you want to call it that.

The reason city-states survived for centuries and prospered depended on several important factors that are worth mentioning. First, they were established in a perfect geographical location by having a sufficient water supply, manageable climate, easy protection from land, enough fertile arable land, and a protected harbor. Some of them were established close to the mines and exported their products throughout the Mediterranean. Those who became prosperous needed more protection than others. In those days there were lots of pirates who made their living just by raiding villages.

City-states also raided each other, and pirates were considered heroes because they brought back bounty to their own city-state. It was common that they would raid each other if there were no treaties in effect. It was good business as long as your own city-state didn’t get raided. Some rich ones had a hideaway mostly in the form of a castle or another village on the hills where it would be hard to reach or be impregnable. Second, these city-states always wanted to be not over 200,000–250,000 people. They knew that if were to become more populous, it would have been difficult to manage the people and to defend the city. Although bigger city-states did exist like Troy, Smyrna, Ephesus, and Mellitus, they were constantly under attack from major invaders from the mainland and from the sea. Their opulence was enticing. For this reason, all four of these city-states were invaded and pillaged. Sometimes the majority of the inhabitants were murdered, buildings were leveled, and the city-states were rebuilt several times. When other city-states were easier to protect or were not getting as much attention, the surviving inhabitants of the invaded city-states would just migrate to them, leaving their own city-states to disintegrate. It was a pragmatic and simple solution, but it worked for thousands of years and produced the arts and crafts, as well as culture, that became the foundation of larger civilizations and nations in the Aegean Sea and the Mediterranean basin. In short, the seeds of Western Civilization, as we call it today, were planted in western Anatolia. They of course derived their culture from the civilizations that had preceded them in central and eastern Anatolia.

Kuşadası was our last anchorage before arriving at Bodrum. All day we had a sailing fiesta on moderately smooth seas with a comfortable reach, making an average of 5.5 to 6.5 knots. When we arrived at Bodrum, it was 19:00 and the day’s run was 74.13 N. miles, averaging a fantastic 5.69 knots.

I had been at Bodrum once before. It was in 1974 when I started my Blue Voyage to Gökova and to Mandalya. I made the trip with Oktay and Aysel Yenal and their daughter Ayşe and son Ali. During this trip, I acquired the desire to see Bodrum and have continued to feed this desire to this day. I remember very clearly that I had no idea and no intentions to come back here to live. Bodrum was just a pleasant memory that one never forgets and surfaces in your mind at every occasion. I didn’t know then what Cevat Şakir said:

“Yokuş başına geldiğinde Bodrumu göreceksin

Sanmaki ayni kişi olarak döneceksin”

(When you come to the top of the hill, you will see Bodrum. When you return,do not think that you will be the same).

At the time I did not know that after my return to the US following this Blue Voyage, the US economy would go into a deep recession, and an unpleasant atmosphere would develop at the office (CHHKK). My relations with my partners would be strained, and finally I would walk out of this partnership. Later when I had doubts, about my decisions about being right or wrong, I asked myself if my memory of Bodrum remained in my subconscious and influenced my future actions at the office. I never had the answer. If I only used my logic I would say, it may have influenced my decision about forty percent. There definitely were other reasons brewing in my mind for a long time.

By that time, we had been in the US for eighteen years. In one hand most of these years Gönül had spent half of the year here, and the other half at the US, However, never was calling the US, her home. On the other hand Cem was attending the University of Maryland and our father and son relations weren’t at its best. I constantly started to get involved with his life when I tried to guide him to the right direction. He was too much under my eyes. At least, at the time, that was my thinking.

My life in the office was making me bitter and irritable. We were five partners, and I was the only non-Jewish one among them. In that sense I was not one of them and I knew if the chips came down, I will be alone, they will go against me, no matter If I was right or wrong. My thinking was different, and my business ethics and ability did not match with their rather lose attitude toward very fundamental management issues. Every night when I would come home, I would be exhausted, upset, and bitter. At home, I dwelled upon my own shortcomings and my unfulfilled expectation from others. This continuous contradiction exasperated me and made me withdraw within myself. I began to ponder living a different life. Turkey would come to my mind.

At the time, everyone was telling me how much opportunity there was in Turkey for me and for Cem. I erroneously thought that I would not need to work if I were in Turkey. However, to develop something for Cem to do was appealing to me. He was majoring in Business Administration and that would put him in the right circles in Turkey. Also a few years away from my influence would probably help him gain his self-confidence.

With all these ideas brewing in my mind, my partners against my advice, started to fire good people while they were keeping some others that were no good at all, because they were Jewish. So when things got really bad at the office, I talked to Gönül about the possibility to pack up and go back to Turkey. At the time, she had the misconception that I made the best decisions, so without too much hesitation she agreed that it may be good for us to go back to Turkey and have a life in Bodrum, at least for a major part of the year.

After that decision, I started to yearn for that peaceful life in Bodrum. I had no idea what was waiting for us. Good or bad, pleasant or unpleasant, healthy or unhealthy—all was in the Pandora’s Box.

We arrived at Bodrum after a nice sail in the late afternoon. We tied up at the Yacht Marina, which was new at the time. The management was simple and the facilities were primitive, but they met our needs. The hour being late I postponed the Customs registration to the following morning. Kazım went to town; I stayed in Kuma.

There were only few boats on the pier. Some passersby looked at me sitting on the quay under the moonlight by myself, but no one really bothered me. The only person I saw that night as soon as we came in was Şakir Sabuncu. I had not seen him for many years. He waved at us from the next pier. After having dinner alone I put my folding chair on the pier and started to absorb the magnificence of the Bodrum Castle under the full moon. It was indeed exquisite. A beauty that I have never grown tired to look at.

However, sitting at that pier alone, that night was the loneliest night of my life. What expected me in Bodrum was a big question mark and if I tell you that I started to have doubts about my being here, I would not be lying. I was lost, and I was scared. At that moment if I had had a magic stick, I would have reversed everything and gone back to Seven Hill Lane to the warmth and security of our house of our established life. I could not help myself remembering that this was the second time I had this very feeling. First, when I went to the US and stayed at Munir’s house in Baltimore on my first night in a strange country, a strange house, and now when I came back to Bodrum alone on the deserted quay.

Did I know what I was doing? Was I a fool making unwise decisions?

I found myself judging me and arriving to a workable conclusion. I was not going in to a depression no matter what. The arrow had left the bow and there was no turning back. So the only way to go was forward as planned and make the best of it, as well as I can. I was not choosing to be a looser and I was going to work for it to become a success.

With these encouraging thoughts, I packed up the chair, went down below and went to bed, hopeful for a better life to come.

Son Yorumlar